Cubed: Bounded-memory serverless array processing in xarray

Wednesday, June 28th, 2023 (over 2 years ago)

TLDR: Xarray can now wrap a range of parallel computation backends, including Cubed, a distributed serverless framework designed to limit memory usage.

Introduction#

One of Xarray's most powerful features is parallel computing on larger-than-memory datasets through its integration with Dask. We love Dask - it's an incredibly powerful tool, a big part of Xarray's appeal, and central to the scalability of the Pangeo stack.

However, the vision of seamlessly processing any array workload at arbitrary scale is incredibly challenging, and its good to explore alternative implementations that might complement Dask's approach.

Cubed is one such alternative - a serverless framework for array processing developed by Tom White. Tom comes to the Xarray community via working on the statistical genetics toolkit, sgkit, and brings with him considerable experience with distributed systems. We will discuss how Cubed works, what its novel design can offer, and demo using it on a realistic problem.

We will also explain how Xarray has been generalized to support wrapping Cubed, opening the door to yet more alternative implementations of chunked parallel array computing in Xarray.

The challenge of managing memory usage#

Managing RAM usage in big computations is very hard. In the wider world there are many different frameworks for performing distributed computations, but most of them can't make strict guarantees about limiting memory usage. In practice this means that configuring workers or adjusting details of the computation plan to avoid accidentally exceeding memory limits is often the bottleneck for getting real-world computations to run successfully.

The Dask developers have been making great progress on this problem, releasing big changes to the distributed scheduler, and recently a new approach to rechunking using a P2P algorithm.

We've been working on a different approach: Cubed's framework is specifically designed from the ground up to avoid this memory problem.

What is Cubed?#

Cubed is a library for processing N-dimensional distributed arrays using a bounded-memory serverless model. What does that mean? Let's take these terms one at a time:

N-dimensional arrays

Cubed provides a cubed.Array class which implements the Python Array API Standard. Like numpy/cupy/dask arrays etc., Cubed arrays understand basic N-dimensional operations such as indexing, aggregations, and linear algebra. Note that Cubed does not understand data structures other than arrays, for example DataFrames.

Distributed

Cubed Arrays are divided into chunks, allowing the work of processing your dataset to be split up and distributed across many machines.

As well as exposing a .chunks attribute in exactly the same way as Dask, cubed provides functions for applying chunk-aware operations such as map_blocks, blockwise, and apply_gufunc. Cubed owes another huge debt to Dask here for developing and exposing these useful abstractions.

Bounded-memory

Cubed aims to perform operations without exceeding a pre-set bound on the total RAM usage of the computation. By building all common chunked array operations out of basic operations with known memory requirements, Cubed guarantees that the entire computation executes in a series of bounded-memory steps.

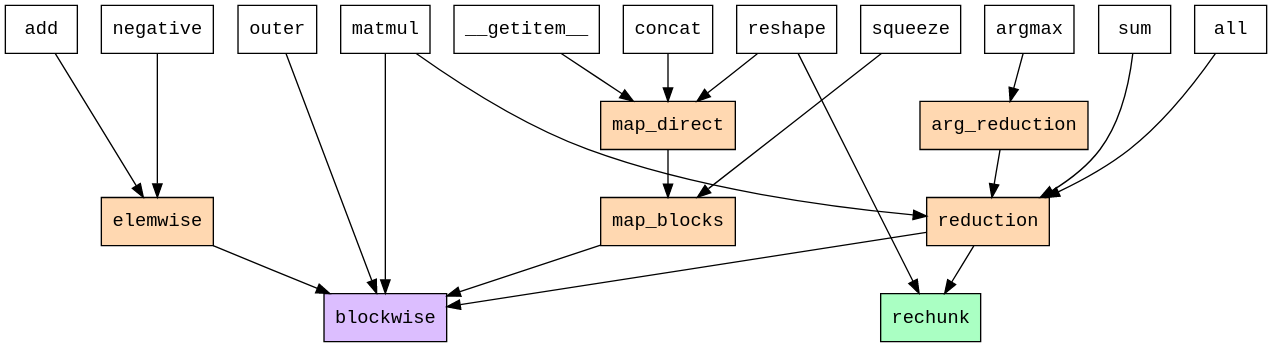

Cubed implements all chunked array operations in terms of just two "primitive operations": blockwise and rechunk. Blockwise applies an in-memory function across multiple blocks of multiple inputs, and can be used to express a range of tensor operations. Rechunk simply changes the chunking pattern of an array without altering its shape.

FIGURE: Dependency tree for chunked array operations within Cubed, from cubed's documentation. Notice that all array API operations (white) can be implemented for chunked arrays in terms of "core ops" (orange) and eventually just two "primitive ops" - blockwise and rechunk.

Both blockwise and rechunk can be performed using algorithms which only require loading one chunk from each input array into memory at any time. In the case of rechunk the algorithm comes from the Pangeo Rechunker package, whose model was a direct inspiration for Cubed. As each chunk is of known size, the RAM usage for processing each chunk can be reliably estimated in advance.

Therefore the expected RAM usage of any Cubed computation can be projected in advance, and compared against the known system resources available (specified via the cubed.Spec object).

Serverless

Serverless computing is a model in which some service runs a users tasks for them on an on-demand basis, allowing the user to avoid worrying about the details of how in fact their tasks are being run on real servers somewhere.

Cubed breaks down every array operation into a set of independent tasks, each of which reads one chunk from cloud storage and operates on it. These tasks are a good fit for a serverless cloud computing model.

However, unlike on a cluster the serverless functions cannot communicate with each other directly over the network. Cubed instead writes an intermediate result to persistent storage between each array operation, saving a history of steps via Zarr. This approach is a generalisation of the way Rechunker's algorithm writes and reads data to an intermediate Zarr store as it executes. (Cubed actually implements some optimizations to avoid writing every intermediate array to disk, but more are possible.)

The benefit of serverless for analytics jobs is that instead of the user creating, managing, and shutting down a cluster manually (which lives either locally or on one or more remote servers), they simply specify the tasks they want performed and hand those tasks off to some paid-for serverless cloud computing service, such as Google Cloud Functions or AWS Lambda. The tradeoff is that this approach is much more I/O intensive, and serverless nodes are generally more expensive than cluster nodes.

Cubed interfaces with a range of serverless cloud services and uses them to execute the chunk-level operations required to process the whole array. This also provides chunk-level parallelism - all the tasks for creating one array are embarrasingly parallel so can be run simultaneously. In other words, if your Cubed operation is writing its result to a Zarr store with 1000 chunks, Cubed will compute that step with 1000 parallel processes simultaneously by default.

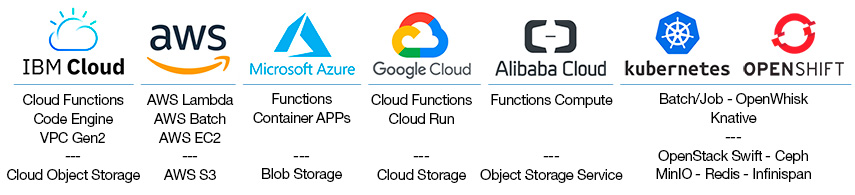

FIGURE: There are a large number of commercial cloud services which offer serverless computing services. All of the services pictured here are supported by the Lithops framework, which is only one of many tools Cubed can use to execute computations. So far, using the Lithops executor, Cubed has been tested on both AWS Lambda and Google Cloud Functions. (It has also been run on AWS using Modal and Dataflow using the Beam executor.)

Sounds cool, how do I try it?#

You can try using Cubed arrays directly or you can use them seamlessly through Xarray, in the same way you use Dask.

First conda install -c conda-forge cubed-xarray, which will install Cubed, the latest version of Xarray (v2023.5.0), and the glue package cubed-xarray.

To run Cubed in serverless mode you need to set up integration with a cloud service. Alternatively you can just run Cubed locally, but you won't see many of the benefits (local execution is the default if you don't specify an executor below).

Before creating a Cubed array you need a Spec, which tells Cubed (a) how much RAM you think a process should need to compute any one chunk, and (b) where to store all the temporary files it will create as it executes. This location can be a local directory or a cloud bucket.

1from cubed import Spec 2 3spec = Spec(work_dir='tmp', allowed_mem='1GB') 4

Now you can create a cubed-backed Xarray object in the same way you would create a dask-backed one:

1ds = open_dataset( 2 'data.zarr', 3 chunked_array_type='cubed', 4 from_array_kwargs={'spec': spec}) 5 chunks={}, 6) 7

The only difference is the addition of the new chunked_array_type kwarg (which defaults to 'dask'), and the new from_array_kwargs dict, which allows passing arbitrary kwargs down to the constructor that creates the underlying chunked array. The chunks kwarg plays exactly the same role as it does when creating Dask arrays. (This also works with the .chunk methods on Dataset/DataArray, using the same keyword arguments.)

Now you specify your analysis using normal Xarray code, right up until you need to compute the result. In a similar way to how Dask's .compute method accepts a scheduler argument, Cubed's .compute accepts an executor argument. You need to specify which executor to use by importing it, and configuration options for the cloud service would also be passed at this point.

1from cubed.runtime.executors.lithops import LithopsDagExecutor 2 3ds.compute(executor=LithopsDagExecutor()) 4

How does this integration work?#

Xarray has been coupled to Dask since 2015. How did we generalize it?

Much of the integration works immediately because Cubed implements the Python Array API Standard, and Xarray can wrap any numpy-like array (see the blog post on wrapping pint.Quantity arrays).

Chunked arrays implement additional attributes (e.g. .chunks) and methods (e.g. .rechunk), but also require special functions (e.g. blockwise, map_blocks) for mapping in-memory numpy functions over different chunks. These key functions are useful abstractions invented within Dask, and Cubed implements its own versions of each of them.

Chunked array implementations specify how to dispatch computations to the correct implementation of these functions by subclassing a new ChunkManagerEntrypoint base class. Any array library implementing an array-like API and defining chunk-aware functions can hook in. Using entrypoints means the possible backends can be automatically discovered, which is why we don't need to explicitly import anything from the cubed-xarray package.

Demo: The "Quadratic Means" problem#

To succinctly demonstrate the relative advantages of Cubed, we'll choose a workload which is representative of what happens when cluster-based frameworks struggle with memory management.

The "Quadratic Means" problem is a simplified version of calculating the cross-product mean from the climatological anomalies of two variables. It requires taking products of two chunked scalar variables $U$ and $V$ and then aggregating the result along the chunked dimension. It is a good example of problem that is simple to express, but creates a dask graph complex enough to trigger suboptimal performance of the distributed scheduler.

Dask results#

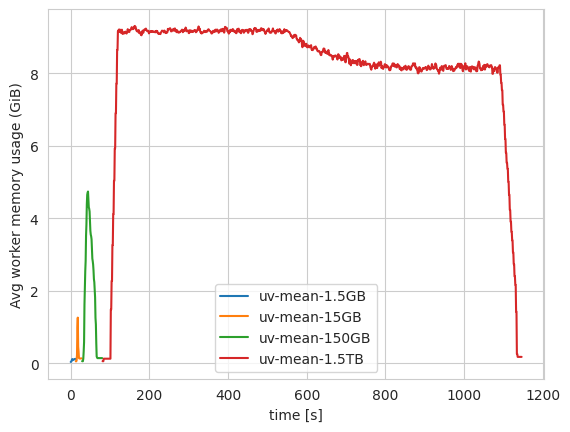

FIGURE: Dask's memory usage for a simplified version of the "quadratic means" workload, at a number of different scales. Notice the RAM usage increasing proportially with dataset size, until the workers spill to disk for the largest dataset (1.5TB). If the workload were much larger, or the cluster much smaller, this would have crashed. This was run on 20 16GB RAM workers using Coiled.

We ran this workload on Coiled, for datasets of increasing size, using the latest version of dask.distributed, both with and without P2P rechunking. We see that as the problem size increases, the peak memory required by the dask cluster increases too. Once the peak memory required is larger than the RAM available to the workers, they continue loading data, but spill it to disk (spilled memory not shown in the plot). If the total memory available is smaller than the dataset size, the cluster will crash (here we used 20 workers to ensure there was enough disk space to complete the 1.5TB workload).

This type of failure occurs sometimes for real array workloads when using dask, but is a symptom of the general difficulty of memory management when using any cluster-based framework. (The performance of on this particular case could almost certainly be improved by changes to dask's distributed scheduler, and indeed dask.distributed has gotten hugely better at memory management recently. Here though we are just using this case as a specific example of a type of failure that is very difficult to solve in general.)

Cubed results#

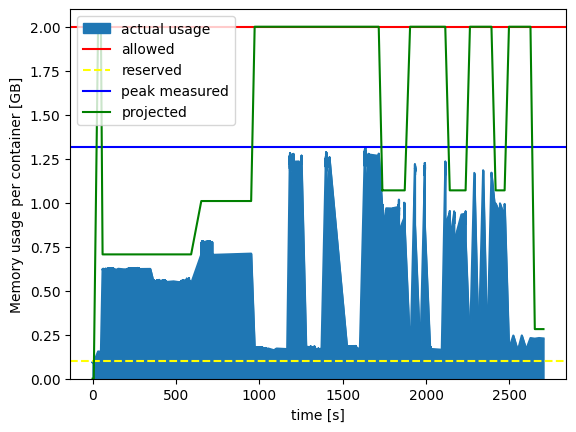

Trying this problem with Cubed (using the Lithops executor and Google Cloud Functions), we find that Cubed successfully completed the workload at all scales, including the 1.5TB workload. Remarkably, it did so using only 1.3GB of RAM per serverless container, staying below the threshold of 2GB we set in the cubed.Spec.

If we take just the largest version of this workload (1.5TB), we can visualize the relationship between the various types of memory Cubed accounts for over the course of the computation.

FIGURE: Cubed's actual memory usage vs projected memory usage, for the largest workload (1.5TB). Cubed successfully processed 1.5TB of data whilst only using a maximum of 1.3GB of RAM per serverless container, staying well below the given limit of 2GB of RAM. This was run using Lithops on Google Cloud Functions, which provisioned thousands of serverless containers each with 2048MB of RAM.

You can see again that the projected memory usage is below the allowed memory usage (else Cubed would have raised an exception before the job even started running), and the actual peak memory used was lower still. We've also plotted the reserved memory, which is a parameter intended to account for the memory usage of the executor itself (i.e. Lithops here), and was estimated by measuring beforehand using cubed.measure_reserved_memory().

One obvious tradeoff for this memory stability is that Cubed took a lot longer to complete - roughly 4x longer then dask for the 1.5TB workload (45m 22s vs 11m 26s). We will come back to discuss this shortly. (EDIT: Since then a lot of work has been put into optimizing Cubed's performance - see the follow-up blog post.)

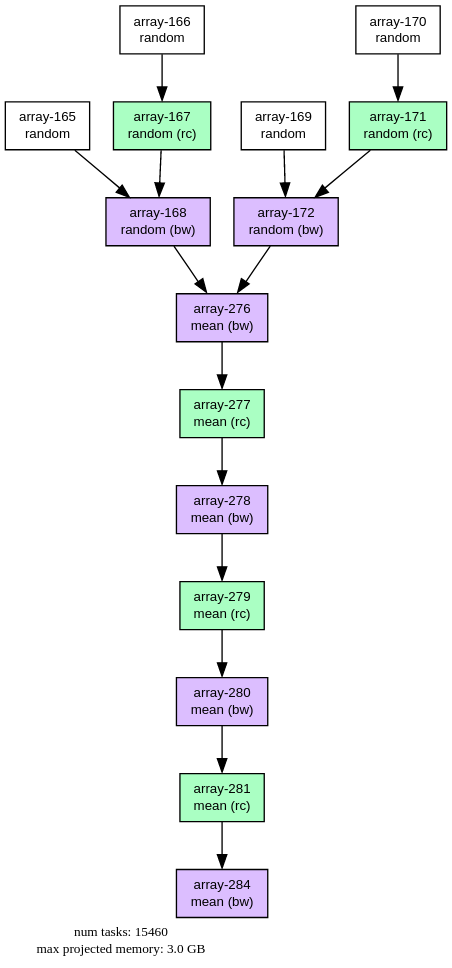

Finally it's interesting to look at Cubed's equivalent of the task graph. To calculate one array (the product $UV$ from the quadratic means problem), Cubed's "Plan" for processing 1.5TB of data looks like this:

FIGURE: Cubed Plan (i.e. task graph) for processing 1.5TB of array data. This graph corresponds to a single xarray variable (UV) in the "quadratic means" workload. Each node corresponds to an intermediate Zarr array that gets written to disk as the computation progresses, separated by either rechunk (rc) or blockwise (bw) steps. Notice that the number of nodes in the graph is not proportional to the number of chunks in the array.

The task graph is at the array-level, meaning that it does not grow proportionally to the number of chunks. The final linear series of steps does get longer with problem scale, but only logarithmically, as it represents the number of steps in a tree-like reduction necessary to reduce that quantity of data. (This Plan is somewhat similar to Dask's "High Level Graph", but array-native, and designed to avoid the problem of over-burdening a scheduler.)

Pros and cons of Cubed's model#

Cubed uses a completely different paradigm to Dask (and other frameworks), and so has various advantages and disadvantages. Let's discuss the obvious disadvantages first.

Disadvantages#

- Writing to persistent storage is slow In general writing and reading to persistent storage (disk or object store) is slow, and doing it repeatedly even more so. Whilst there is scope for considerable optimization within Cubed (EDIT: see the follow-up blog post for subsequent performance improvements), the model of communicating between processes by writing to disk will likely always be slower for many problems than communicating using RAM like dask does. One idea for mitigating this might be to use a very fast storage technology like Redis to store intermediate results.

- Spinning up cloud services can be slow There is also a time cost to spinning up the containers in which each task is performed, which can vary considerably between cloud services.

- Higher monetary cost We estimate that Cubed cost about an order of magnitude more to run than Dask on Coiled did for this 1.5TB workload (order $10 vs order $1). Specific numbers and lengthier discussion are given in the accompanying notebook. This is not very suprising, but the lesson should also be that (like performance) estimating cloud costs is complicated, workload-specific, provider-specific, and contextual. It is also worth noting that costs for both could be lowered. Future optimizations to Cubed could reduce the number of intermediate Zarr steps required, and in a serverless paradigm you cannot accidentally be charged for a cluster you leave running idle. On the other hand Coiled can use ARM chips, as well as spot instances, both of which could lower its cost further.

- Still a prototype Cubed is still young, and whilst fairly feature-complete it has not been rigorously tested on very large datasets, or on several of the cloud services it could theoretically run on. There will be bugs, or things which are simply not yet implemented. The cubed-xarray integration is similarly experimental, and any present incompatibilities will likely cause silent coercion to numpy arrays. Contributions to Cubed to are welcome!

- Only array processing Cubed is far less general than other parallel processing frameworks like Dask, Spark, or Apache Beam. It only supports array processing, and cannot support other data structures like Dataframes, custom collections, or arbitrary computation graphs.

Advantages#

- Bounded-memory We've already seen how this works, but being able to complete a large-scale job that previously crashed or had to be manually split up would be an extremely useful feature on its own.

- Resumable Saving each intermediate result to disk means the progress of the computation is saved even if the cluster goes down or power is lost. Cubed allows you to resume a stalled computation in a new process to finish a long job.

- No cluster to manage A serverless design means that the user does not having to deploy and manage a cluster at all. Arguably conceptually simpler, this model also means less boilerplate code, no error-prone deployment step, and only paying for computation you actually do, not for the time the cluster is up.

- Horizontal scalability Cubed is designed with "horizontal scaling" in mind, meaning bringing many machines to bear on the problem at once. (As opposed to "vertical scaling" - utilizing a bigger machine.) Zarr can support as many concurrent writes as there are chunks, and the serverless framework should be able to smoothly launch and manage almost any number of parallel workers. This has yet to be tested at truly massive scale however. Cubed also avoids another potential scaling bottleneck of having too many individual tasks for a single scheduler process to manage. The computation is represented as an array-level graph, so the graph size doesn't scale with the number of chunks, and there is no complex scheduler to over-burden.

- Various runtimes Cubed can execute its computation plans using a range of executors, opening up a big space of possibilities. As well as running locally, Cubed can convert its plans into Beam Pipelines and run on Google Cloud Dataflow, use Lithops to dispatch to a range of serverless providers, or use the Modal client to start-up containers in literally a second. It should even be possible to write a Dask executor for Cubed, similar to what exists in the Rechunker package. This might go some way to giving the benefits of Cubed but with lower cost and speed. One could also imagine running Cubed on another type of cluster.

Overall one could think of different parallel array processing libraries as complementary, best-suited to different problems or to running on different systems.

Range of options#

There is a saying that there are only three important numbers in programming: 0, 1, and infinity. Having gone from 1 to 2 options of parallel backends, can we go to N?

That is the situation in the database analytics world. There SQL (Structured Query Language) queries form a common high-level way of expressing user intent, but the actual execution of a query on a database can be performed using a huge range of technologies, known as Query Engines. These projects compete to determine which can get the best performance on various standardised benchmarks. In the example above Xarray is playing a similar role to SQL as a high-level query language, allowing users to easily try out different array backends depending on their problem.

Here we've focused on Cubed, but this work opens the door to using other alternative distributed array processing frameworks such as Ramba, Arkouda, Aesara, or even others yet to be developed... We're discussing this dream in the Pangeo Distributed Arrays Working Group, so if this inspires you then please join us!

Conclusion#

- Xarray can now wrap multiple chunked array backends.

- Cubed is a serverless prototype which you can try out today.

- We hope this integration work leads to a range of new parallel backend options for users.

- Please come and help out on the Cubed repository, and join the Distributed Arrays Working Group!

Acknowledgements#

Tom Nicholas' work on this project was by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Data-Driven Discovery program, via a grant to the Columbia Climate Data Science Lab.